Doctor. Doctor. Synonymous with prestige, social respect and financial stability. At least, this is how it looks in the popular consciousness, fuelled by TV series where brilliant diagnosticians in perfectly pressed outfits save lives at the last second.

The reality is different. Less spectacular, and infinitely more challenging.

The road to becoming a doctor in Poland is not a sprint. It is a brutal, multi-stage marathon, taking 12, 15 or sometimes more years. It is a journey measured not by money earned, but by thousands of sleepless nights, gigantic stress, hundreds of exams and making life-and-death decisions, often for a salary inadequate to the responsibility.

As a brand that has the privilege of dressing these professionals on a daily basis, we feel obliged to show what this path really looks like. It's a story of dedication, passion and superhuman determination.

Myth vs. Reality: What Does it Really Mean to „Be a Doctor”?

Before going through the stages of education, we need to dispel the biggest myth: money and prestige. The young doctor, just out of university and internship, entering the specialisation system, is one of the hardest working and at the same time least paid (in relation to competence) professionals.

True „career” and „stability” is deferred gratification. Before a 35-year-old specialist can open a private practice, he has to go through the hell of residency - a period when his peers in IT or finance are already building their lives, while he is still studying for the next exam after a 30-hour on-call. This job is a calling, but a calling based on titanic work.

Stage 1: Selection. Six Years of Medical Studies

It all starts with the baccalaureate exam. The medical faculties at renowned medical universities (such as Warsaw, Gdansk, Krakow or Poznan) are almost exclusively attended by olympians and people with 95-100% results in extended biology and chemistry. The competition is brutal. This is the first filter.

If you think the baccalaureate was difficult, studying medicine is a whole different level. It's six years (12 semesters) of relentless, memorised cramming.

First Impact: Anatomy and Prosectorium

The first two years are the so-called „big sieve”. These are theoretical subjects designed to sift out those who are not up to the pressure. The symbol of this stage is anatomy. Hours spent in the dissecting room, learning every bone, muscle, nerve and blood vessel in Latin. Plus biochemistry (hundreds of metabolic cycles) and physiology (how each system works).

The anatomy exam, the famous „pins” (identifying structures on slides), is the stuff of legend and trauma for every doctor. Anyone who fails this stage is out.

The Next Years: From Theory to Clinic

After passing the theory, students enter the clinical departments. They begin to learn internal medicine, surgery, paediatrics, gynaecology, psychiatry, neurology... It's another four years of learning about thousands of diseases, their symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. A student's day looks like this: 8:00-15:00 clinical classes in the hospital, 16:00-24:00 home study for the next day. And so on for six years.

Stage 2: LEK - The Examination That Decides Life

After six years and a diploma, the student is not yet a doctor. He or she is a „doctor without a licence to practise”. In order to obtain one, he or she must pass the Medical Final Examination (LEK).

That's 200 test questions from the entire six years of knowledge. But „passing” (56%) is not everything. The result of this one exam, expressed as a percentage, determines the entire przyszł. It determines whether a young doctor will get into the specialisation of his or her dreams. Whoever wants to become a cardiologist or a plastic surgeon must have a score around 90% and above. The pressure is unimaginable.

Stage 3: Purgatory. 13-Month Postgraduate Internship

After passing the LEK, the young człowie receives a „Restricted License to Practice” and goes on to postgraduate traineeship. It lasts for 13 months.

This is the first time she has realistically worked as a doctor, but under close supervision. He goes through all the key departments: internal medicine, surgery, paediatrics, gynaecology, ED and family medicine. This is his first contact with real responsibility, bureaucracy (filling in records) and... his first salary. The trainee's salary, which is symbolic and often lower than the national minimum wage.

After 13 months of internship and passing the final (oral) exam, the young doctor finally receives a full Right to practise (PWZ). He is about 26-27 years old. And this is where the real work begins.

Stage 4: Marathon proper - Specialisation (5-7 years)

Having a PWZ means that you are a „general practitioner”. But in modern medicine, that's not enough. Now is the time to choose your path - specialisation. This is a process that in Poland takes (depending on the field) from 5 (e.g. internal medicine, paediatrics) to 7-8 years (neurosurgery, cardiac surgery).

This is the hardest period in a doctor's life. This is the stage of the so-called 'in-between'. residencies.

A resident doctor is a doctor in the process of specialising. He works full-time in a hospital ward, learning his field. But his job is not only about learning. It is, above all:

„On-call” - The Bane of the System

The resident doctor, in addition to his or her normal 8am to 4pm work, must perform medical on-call duty. This means he stays in hospital for another 16 hours (and sometimes longer), working a total of 24, 30 and sometimes 40 hours without sleep.

It is on these on-call duties, in the middle of the night, under gigantic pressure and in permanent fatigue, that young doctors learn the most. They have to make decisions in the ED on their own (albeit on call from a specialist), deliver babies or assist in emergency operations.

Two Stations - Sad Standard

The residency salary, although guaranteed by the Ministry of Health, is low in relation to the responsibility. It is therefore the absolute norm for a young doctor to work several jobs in order to support his family (after all, he is already closer to 30). In his „home” hospital, he does his specialisation, and at weekends and on „off-call” nights, he earns extra money at the Medical Night Service, in the ED in another city or in a private clinic.

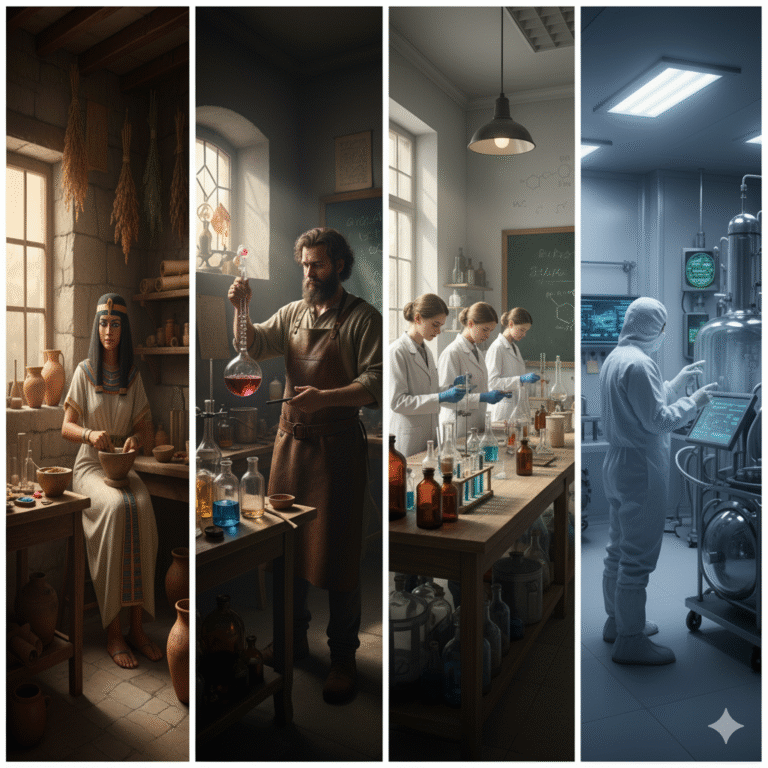

Evolution of the Professional: From Apron to Ergonomic Scrubs

This gigantic change in the mode of work - from „Mr Doctor” working from 8am to 3pm, to the modern-day „resident” living 30 hours at a hospital - has necessitated a revolution in dress.

Historically, the symbol of the doctor was white, stiff, starched apron. It was a symbol of status, authority and ... distance. Such an apron was great for rounds, but a nightmare for real work. It was cumbersome when resuscitating patients, uncomfortable when assisting 12-hour operations and impractical for night duty.

The revolution przyszła of operating theatres. Surgeons have long known that something different is needed for hours of precise work. They need scrubs.

Medical Scrubs - New Generation Uniform

Initially green or blue scrubs used to be reserved only for the operating theatre. Today, they have become the uniform of the entire hospital. Why?

- Ergonomics and Comfort: Working 24 hours requires an outfit that „doesn't exist”. Modern

medical scrubsis made of flexible, breathable materials (such as polyester/viscose/elastane blends). It does not restrict movement, wicks away moisture and is soft - unlike the stiff cotton of the old aprons. - Functionality: The doctor must carry a stethoscope, telephone, stamp, pen, notebook, neurological hammer. The old apron had two pockets. Modern

medical scrubs(and sweatshirts and trousers) have 5, 7 and sometimes 9 of them. They are deep, reinforced and strategically placed. - Psychology:

Scrubsdemocratised the hospital. It obliterated the rigid hierarchy. Today, both the head professor and the resident doctor wear the same type of outfit. They are one team. It's also a manifestation - „we are people of action, we are ready to work”.

For the modern doctor, who spends more time in hospital than in their own home, choosing the right scrubs This is not a question of fashion. It is a fundamental question of ergonomics and mental hygiene.

Stage 5: PES - Final Examination

After 5-7 years of hard work on the ward, dozens of courses, conferences and hundreds of on-calls, the resident approaches the PES - State Specialist Examination.

This is another killer exam (oral and written) of all the knowledge in a particular field. Only passing it gives the doctor the title specialist (e.g. cardiology specialist, general surgery specialist).

The doctor is then 32-35 years old on average. After 13-15 years after matriculation, he is finally a „fully-fledged” doctor in his field.

Life after the „Marathon”: What Next?

Becoming a specialist opens all doors. Now a doctor can:

- Continue working at the hospital as a „senior assistant” and, in time, become Head of Department.

- Open your own private practice or clinic.

- Go in a scientific direction, doing a doctorate (MD) and habilitation.

Most specialists combine these paths - working part-time in a hospital (to keep in touch with the toughest cases and not lose their „hand”), while also running a private practice.

Real Earnings: Was It Worth It?

And what about the mythical wages? They are extremely polarised in Poland.

- Intern: He earns the minimum wage or less.

- Resident: He earns a guaranteed salary (several thousand złotas net), which is low in relation to the responsibility. Therefore, he makes extra money on call, often doubling his salary, but at the expense of his private life.

- Specialist in a public hospital: It earns a solid salary, but still often disproportionate to the responsibility.

- Specialist in the private sector: This is where salaries are highest. A specialist in a sought-after field (dermatology, ophthalmology, orthopaedics), running his own clinic, can earn tens of thousands of złotych per month.

But let's remember: these top earnings are the fruit of the 20 years extremely hard study and work, gigantic costs (third-party insurance, equipment) and working 60-70 hours a week.

Summary: A Vocation Based on Sacrifice

The path of a doctor is an endless marathon. It is a choice of a life of constant learning, under pressure of time and responsibility for human life. It is a profession that requires not only outstanding intelligence but, above all, inhuman mental and physical resilience.

The next time you see a doctor who, after 20 hours on call, in his comfortable scrubs, still has the strength to smile at a patient - appreciate that. This is not just a job. It is a vocation for which the highest price is paid.

Respect your doctors. Their journey to where they are has been unimaginably hard. Trust and collaboration is the foundation of treatment.

And if you are on this path - student, intern, resident, specialist - we thank you for your work. We understand your effort. We know that your outfit is your second skin. Check out the collection medical scrubs Scrabme. We created them to keep up with you and your passion.